01 Mar Inflated Inflation Fears

As we wrote last month, a driving component of the increase in volatility in the markets was the expectation of increasing inflation. Wall Street was worried higher inflation would force the Federal Reserve to raise U.S. interest rates more aggressively, resulting in an increase in the cost of capital (possibly causing a shift of money into bonds) and potentially smothering our economic expansion. Inflation erodes the purchasing power of a bond’s future cash flows: the higher the current rate of inflation and the higher the (expected) future rates of inflation, the higher the yields will rise across the yield curve. Investors will demand this higher yield to compensate for inflation risk.

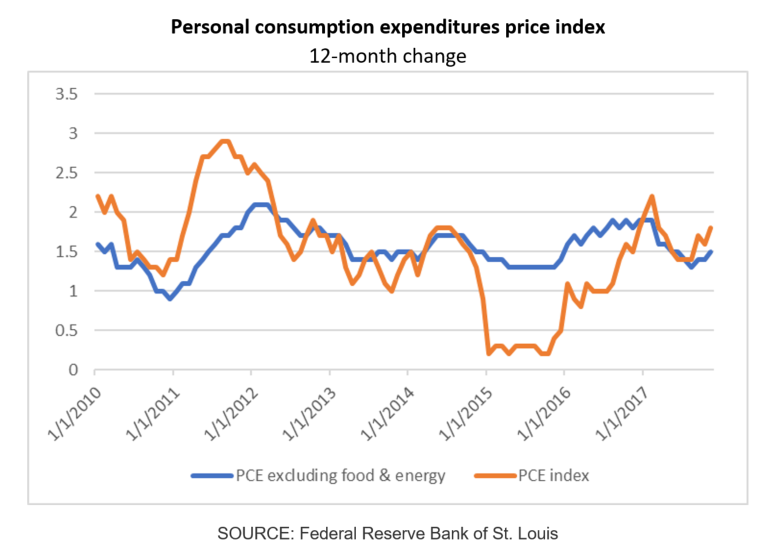

After years of deflationary fears and despite the repeated efforts of central bank policies, we have begun to see inflation concerns appear in the headlines. Inflation is defined as a sustained increase in the general level of prices for goods and services. In the simplest form, increasing inflation means it costs more to purchase a box of cereal today than it did last month. When conducting monetary policy, central banks use inflation gauges such as the consumer price index (CPI) or the personal consumption expenditures price index (PCE). The PCE is the preferred index used by the Fed and ultimately influences the decision to expand or contract the money supply.

The Fed pursued an unofficial 2% inflation target for many years prior to its official announcement of that rate in January 2012—and it has missed that target for six straight years. The most recent Core Consumer Price Index (excluding food and energy) release was 1.82%. Personal consumption data showed signs of gradually firming inflation with the month-over-month headline and core measures both up 0.4% and 0.3%, respectively. However, it still was not enough to move the year-over-year readings, which stayed steady at 1.7% and 1.5%. These results are in line with the Fed’s outlook that inflation should gradually move upward toward their 2% target this year.

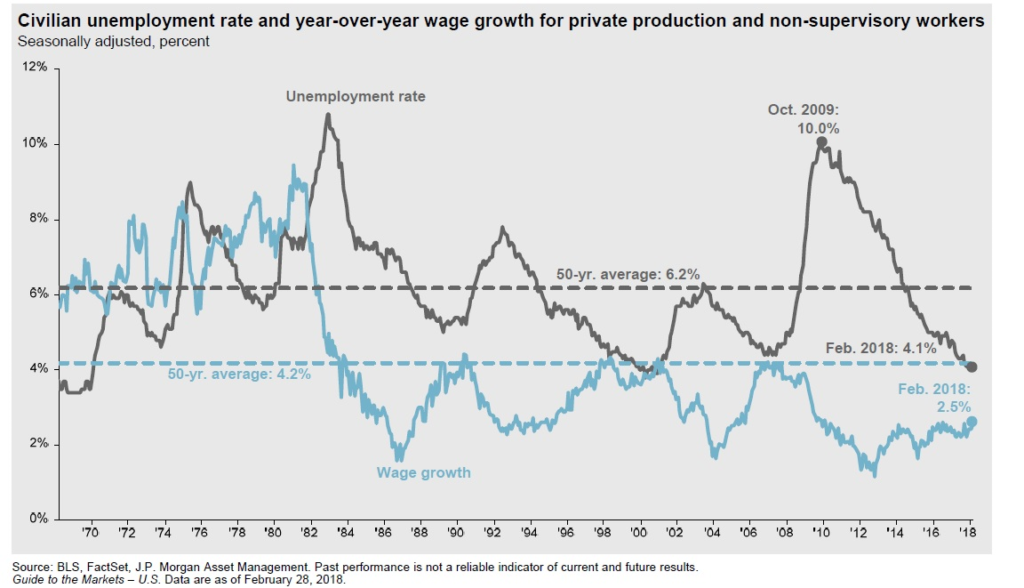

The recent headline of higher inflation expectations was fueled by last month’s better-than-expected jobs report which indicated average hourly earnings increased 2.8% in January from a year earlier, the biggest annual jump since 2009.

The recent headline of higher inflation expectations was fueled by last month’s better-than-expected jobs report which indicated average hourly earnings increased 2.8% in January from a year earlier, the biggest annual jump since 2009.

Wage growth has been in focus because of its stagnation during the current economic expansion. With any uptick in wages, investors expect that inflation will soon follow. But, as you can see below, wage growth for private production and non-supervisory workers still sits below historical averages despite where we are in the current cycle.

However, we believe inflation fears are unfounded and that rising interest rates due to higher inflation expectations don’t tell the complete story. Yes, the jobs report was better than expected—but we would classify it as neutral when looking beyond the non-farm payrolls. Economists had forecasted a gain of 200,000 in non-farm payrolls, a 4.0% unemployment rate, a 2.6% year-over-year increase in average hourly earnings and an average workweek of 34.5 hours. Jobs growth crushed expectations with a 313,000 increase in the month of February, but unemployment fell short, remaining at 4.1%. Average hourly earnings and average workweek duration were in line with expectations. Although a tighter labor market is expected to produce better wage growth, last month wages grew at a slower rate when compared with January. Initially, investors were concerned that bigger paychecks, along with the recent tax reform, would lead to higher inflation.

In addition, most of the recent increases in interest rates are not due to higher inflation expectations: Since the end of last year, the yield on the 10-year nominal Treasury bond has risen by 50 basis points, from 2.40% to 2.90% at the time of this writing. However, over the same period, the 10-year Treasury Inflation Protected Security (or TIP), has seen its real yield rise by 32 basis points, from 0.44% to 0.76%. In other words, 73% of the increase in 10-year nominal bond yield was due to an increase in real yields, not inflation expectations.

We recognize that inflation forces are firming relative to the deflationary environment we’ve experienced over the past couple of years, but do not think that we are going to see runaway inflation. We believe last month’s reaction was an overreaction, and that there are several structural forces that are keeping inflation in check, and that those forces will remain for the rest of the year. We are cognizant of the fact that we are only a quarter of the way into 2018, and that we should be seeing more inflation at this stage of the economic cycle. The seeds have been planted but have barely sprouted.

At Maclendon, we agree with many economists and market strategists that the fears about inflation are overblown. While inflation should increase to around 2%—give or take a few basis points in 2018—we believe it is unlikely to quickly rise much further or drastically overshoot the Fed target.